On Holocaust Remembrance Day, Here is My Family's Story

To all those who suffered and were murdered in the Shoah, may their memories be a blessing.

On International Holocaust Remembrance Day, here is my family’s Holocaust story. This story is based on memories passed on to me by my grandfather and by my great-uncle Charles, who went back to Hungary after the war, but changed his name to Lukacs, which sounded less Jewish. Charles became a journalist in postwar Hungary, and many relatives said that I take after him. My grandfather helped Charles get out in 1956 during the Soviet invasion, and he Americanized his name to Lucas. I spent a lot of time with my great-uncle Charles before he passed away in his 90s. It’s where I get a lot of my firsthand information about the Holocaust.

It was in 1939 that Charles put a four-year-old Andrew Lovy—my father—on a train heading west out of Budapest. He was accompanied by my grandmother Elza. They both later joined my grandfather, who had gone on ahead to America to establish a life there. My grandparents didn’t have to see the crematoria to know that they were waiting for them. I owe my existence to the far-sightedness of my Grandpa Joe, who got out in time. But, his is a different story to tell. Here is where it begins.

Hungarian Jews sat out most of the war in relative peace, although with increasingly draconian anti-Jewish laws passed. Hungarian ruler Admiral Horthy was allied with the Germans, but would not do the Nazis’ bidding when it came to the Jews. At least, not yet.

But toward the end of the war—when Horthy knew it was lost—he tried to make a separate peace with the Russians, who were already on Hungary’s doorstep. So, on October 15, 1944, the day Horthy was to announce his surrender to the Russians, the Germans stepped in and installed a Nazi puppet regime run by the viciously anti-Semitic Arrow Cross.

Then the familiar pattern began. First, influential Jews were stripped of their government and teaching positions. Next, Jewish businesses were smashed, looted, burned, or confiscated. Then Jews were stripped of all their possessions, rounded up and, starving, forced into cramped and disease-ridden ghettos. Entire villages in the Hungarian countryside were drained of their Jews, who were transported to Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, or Mauthausen.

Already, most of European Jewry had been murdered. The world knew that Hungary was next—including Franklin Roosevelt. There were formal protests, and attempts to make secret deals to save the lives of a few Jews here and there, but the Allies—by then firmly superior in the air and on the ground—did nothing to save the Hungarian Jews.

The world watched.

Death-camp deportations and mass executions of Hungarian Jews were recorded matter-of-factly on the inside pages of the New York Times.

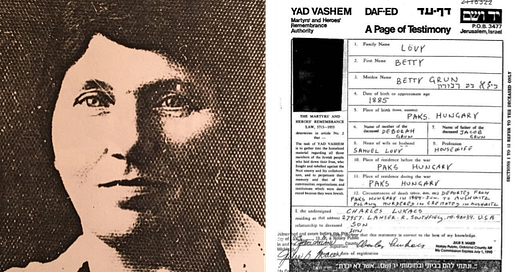

Sometime in the summer of 1944, my great-grandmother Betty Lövy—a deeply religious woman who came from a long line of rabbis and Jewish scholars—was placed in a cattle car, taken to Auschwitz, and murdered in a gas chamber. Here is her Page of Testimony at Yad Vashem.

In Czechoslovakia, the word came out that it was now safe for the surviving Jews to come out of hiding. My great-aunt Hedwig, her husband, and two children believed it. They, too, were handed over to the Germans and murdered.

They were taken to the border of Austria and made to dig anti-tank trenches to try and slow the Russian army. The conditions were appalling, as sadistic German guards murdered Jews at random and threw their bodies in the trenches dug by the victims.

My uncles Andor and Charles were able-bodied men, so they were used as slave labor. By the end of 1944, they were marched from one camp to another, just a few steps ahead of the advancing Allies. They were taken to the border of Austria and made to dig anti-tank trenches to try and slow the Russian army. The conditions were appalling, as sadistic German guards murdered Jews at random and threw their bodies in the trenches dug by the victims.

It was by chance that Andor, in a separate death march, met up with his brother Charles. They marched together for a while. But soldiers of the nearly defeated German army were firing random machine-gun volleys into the marchers. My uncles decided it would be best if they split apart, so one of them would have a better chance of surviving until liberation.

They were right. Andor fell when one of his German guards opened fire. He would have been killed, but the Germans were in a hurry at this point. He heard one of the say, “Don’t waste a bullet on him. He’s dead already.”

Charles found Andor critically wounded, but alive, among a heap of bullet-ridden bodies. Charles picked his brother up and helped him continue to the march to the Mauthausen concentration camp. There, despite horrible deprivations and abuse, he was able to nurse Andor back to health and wait it out until Americans came six months later.

After the war, Andor testified against one of his Mauthausen guards, who was hanged for his crimes.

A few relatives survived Auschwitz and were sent to displaced persons camps. Many immigrated to Israel, but the trauma continued. An uncle could not cope with the memories of Auschwitz and committed suicide. My brother is named for him.

The Holocaust story involving my family is both unusual in its cruelty, but not so unusual in the context of the Holocaust. Many families suffered worse. Life-and-death decisions that would impact the existence of future generations were made in split seconds.

Today, on Holocaust Remembrance Day, and almost every day, I try to live my life knowing of the sacrifices so many made so that I can live a life of relative peace. To all those who suffered and were murdered in the Shoah, may their memories be a blessing.