An edited version of this piece appeared in Longreads back in 2018, but I’m going to run the entire account here. I’ve been working on my family’s story for a number of years and I’d like this Substack to be its home until I can gather it together into a book or in other material I’m working on.

This account is based on writings given to my brothers and me by my grandfather. It is all based on real events, but I’ve invented dialogue and details to bring it all alive. I suppose you could call it Creative Nonfiction, but none of the incidents here are invented.

These are memories I inherited from my grandfather of a pogrom and blood libel from more than 100 years ago. This will be part of an ongoing series in this newsletter.

On the banks of the Danube, there is a place where the great river takes two sharp 45-degree turns, making it difficult for ships to pass unseen. For centuries, this feature made the city, nestled within, a fortification against foreign attack. But from an enemy inside the city’s own boundaries, there was no natural protection. And for a 9-year-old boy, hiding as his neighbors ransacked his grandparents’ home, a wine barrel was the only shelter. There he hid, silent, while around him echoed the muffled, angry, anguished sounds of a pogrom.

The year was 1918 and the place on the Danube was the Hungarian city of Paks, where the local townspeople, having endured defeat in the Great War, were venting their rage on the usual cause of all their woes — their Jewish neighbors. The boy in the barrel was Jóska Lovy. Decades, lifetimes later in America, he will be known as Grandpa Joe and the beloved patriarch of an exponentially expanding family of Lovys — of doctors and engineers, of entrepreneurs and soldiers and writers — scattered across their adopted nation.

But, for now, that future was only as thick as the wood surrounding Jóska and his brother Andor, whose grandparents Jacob and Deborah Grun believed to be safe inside these barrels. They knew the casks would not be destroyed by the mob. The goyim would still need them for the coming grape harvest even if they succeeded in slitting the throat of every Jew in Paks.

Jóska cowered inside the wine barrel, surrounded by near total darkness, yet his senses were assaulted with contradictions. First, was the scent of old oak mixed with the sweet memory of Pesach. The residual smell of wine soaked into the oak barrel in which he hid helped him recall the laughter of family at Passover, the taste of holiday chocolates, the mild intoxication of his grape juice spiked with a touch of the sweet alcohol. Last year was the first seder in which he was allowed to pour a drop of wine into his cup, and he savored the knowledge that, if he drank enough of it, he would grow giddy with drunkenness, the way he heard his adults long after he was supposed to have been asleep.

Jóska had always thought of drunkenness as synonymous with silliness, or happiness — the way he heard them sing Chad Gadya for 20 verses that Pesach evening, the words progressively more slurred, the lyrics, changed from the usual “one only kid” to something more bawdy. It was a jumping, spinning, joyful and Jewish, therefore holy, drunkenness — one that always seemed festive and light and innocent and harmless. He would never have thought to tie the two together: drunkenness and violence.

Tonight, though, as he he hid, silent, he heard the sounds of a different kind of drunkenness, one that he had not known existed. Wine was for holidays, for festivals — for warm Pesach and giddy Purim. What holiday this was, he couldn’t tell.

Outside the courtyard, he heard the mob approaching, hurtling rocks and chanting “Dirty Jew!” and other epithets, many of which he did not understand. Jóska peered out the cork holes that framed the bizarre, terrifying images he was witnessing. Jóska could see women being beaten, their clothes ripped off, the beards of the men plucked. He closed his eyes when they were dragged out into the street and whipped.

“Through the cork holes,” said Jóska grandmother, her voice maintaining its gentle timbre, but slightly more hurried and high-pitched — just enough of a difference to let her grandsons know that this was not the time to question, but to obey. At the same time, her voice also maintained an even calmness so as not to panic the boys.

Windows shattered, distant fires snapped, and deranged laughter came very near his barrel, then dopplered to the left and far away. Looking through the cork hole, it wasn’t so much what he saw that was terrifying — an angry or frightened face here, shards of glass there — but it was what he heard. The incomprehensible sounds of terror among familiar voices. Jóska looked out his peephole and recognized some of his neighbors darting by, carrying paintings, silverware, even clothing. The night came, and as the air filled with the sound of drunken hate songs mixed with Jewish pleadings for mercy, Jóska curled up inside his wooden cask and drifted off to sleep.

He awoke some time later, he did not know how long, to the sound of an enormous crash. The mob had reached his grandparents’ house and they were ransacking it. Through the cork hole, the darkness revealed the flames emanating from the Jewish homes and stores. Across the street, a Jewish-owned grocery store was on fire. He was actually relieved to see the smoke and flames. That meant he no longer needed to be ashamed of his tears. If he was pulled out from the barrel by the goyim, and if they mock him for crying while they beat him, he could tell them the tears were from the smoke and not from their blows.

While imagining he could be so brave soothed him, Jóska wished he could run upstairs to his grandfather’s room and fetch the “magic yarmulke.” It always sounded ridiculous when his grandpa called it that, but its magic was real. It had kabbalistic inscriptions written on it, and it was said to have healed his father when he was a baby. It was given to the family by Reb Rubin, a famous Chasidic rabbi who had attended Yeshiva with Jóska’s grandfather. Jóska was told that when his father was an infant, he became very ill and the rabbi was called to the house to perform one of his mystic miracles. As required by custom, the reb changed the baby’s name, put a beaded yarmulke on his head, and Jóska’s father was healed. Jóska had often thought of that kippah. He didn’t believe in mystical Judaism. He felt there must be a more-logical explanation.

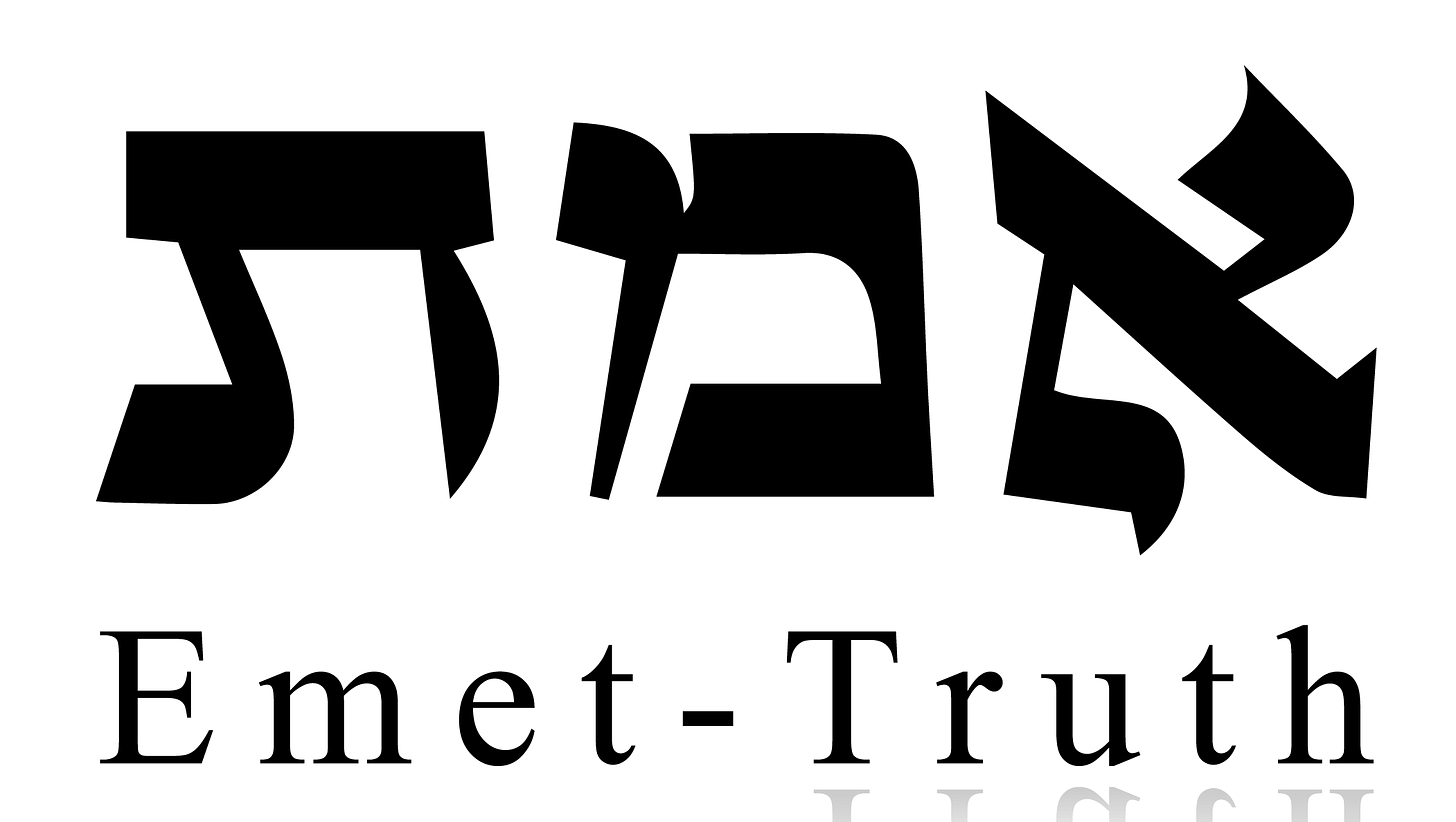

Anyway, he was not certain how the magic yarmulke could help in this situation, but there was no telling what other properties it might contain. Everything was connected in some way if you looked deeply enough. After all, an ancestor of his, Rabbi Yehudah Loew of Prague, had simply placed one word “emet” on a lump of clay, and the clay became a protector of the Jewish people.

But he had no magic yarmulke, no science, no golem, although he whispered it three times. “Emet, Emet, Emet.”

“Truth, Truth, Truth.”

***

Jóska slept again for a time. What woke him was silence. Gone were the screams of pain, the smashing of windows. There were just voices. Calmer voices, voices with familiar accents. Spying through his cork hole, Jóska exhaled loudly and praised God. With one eye, framed by the oak circle from which he peered, he saw Jews. Jews with uniforms. Jews who had served Hungary in the Great War. He saw Jews with guns.

Then, within minutes, he his brother were told that it was safe to come out of their hiding places. The first sensation was the overpowering burning scent. Inside the barrel, Jóska had smelled old wine and wood, but now that he was out, and his senses reached a state of equilibrium, the smoke was overpowering. It filled his eyes, forcing a few coughs and sneezes. Across the street, he saw the charred, collapsed wreckage of the Jewish-owned grocery store.

Sitting outside were the proprietor and his wife, their faces marked with dried blood that had dripped from head wounds. They had been dragged outside by the mob, and beaten in front of their children. It was an odd sight for Jóska, seeing these adults, these friends of the family, their neighbors, with their altered faces. It wasn’t just the blood that was unusual, but their dazed expressions. They were not crying out in pain, they did not even appear humiliated or embarrassed to be seen in such a condition. They simply appeared to be numb, their expressions blank — containing neither scowls nor the warm smiles with which they had always greeted him. Jóska had heard his grandparents speak of them in only terms of respect. They issued credit to those who needed it, whether the customers were Jews or not. But, last night, during the pogrom, all of that was forgotten and they were simply Jews. And, in Hungary, in 1918, a Jew was not a human being during the length of time it took for a mob to vent its rage at their own helplessness in the face of forces outside their control. The Jews were here, and they were alien, even if they were their trusted shopkeepers. It was as if a switch had gone off inside his gentile neighbors and they, too, were no longer human. They were monsters. For the first time, but certainly not the last, Jóska wondered what tells the human mind when to switch into this monster mode.

Was there a magic word that did it, the way “emet” switched on the Golem?

***

The city was unrecognizable. Every Jewish house, every Jewish store, had been looted, windows broken. Merchandise not stolen was left out in the streets, ruined. No home, no business belonging to the Jewish community of Paks was left untouched. Jóska went with his grandfather to the Paks synagogue. His grandfather pointed out the bullet holes and broken windows. Dazed, squinting in the morning light, the yeshiva students — along with their teachers and families — stumbled out of the still-sturdy synagogue, disoriented but alive. The walls and doors held and the mob had not rampaged inside. As pogroms go, the Jews of within the city had been relatively lucky.

In the surrounding small villages, though, reports came in of wholesale murders of Jews in the streets. After only a few days, Jóska saw the refugees pouring into Paks. Many of them looked like the dazed storekeeper he had seen after he’d exited the wine barrel. Their faces were expressionless. No sadness, no laughter, just a stare, and he could not tell if it was focused on something closeby or far away. They came in wagons and on foot, some injured and wearing rags. After burying their dead, salvaging what was left from many generations of savings, they came to the big city to start a new life. The Jews of Paks took them into their homes.

About 200 miles to the east of Paks is the town of Tămașda, where Jóska was born and where he spent the first seven years of his life before moving in with his maternal grandparents in Paks to begin his Jewish education. After the violence in Paks, it was thought that city was now relatively safe compared to the smaller towns, where the Jews were more vulnerable. So, Jóska’s mother and father brought their daughter, Hedwig, and baby boy, Charles, from Tămașda to Paks to join him and Andor. The whole family was together, briefly, and Jóska reveled in family laughter and stories. Nobody discussed what lay below the surface, though. Jóska never told anybody how terrified he felt, hiding in the wine cask during the pogrom.

“Hey, Jóska,” said his sister, Hedwig, through the side of her mouth. Hedwig was a lovely girl with blond hair and an adventurous spirit. “The boys dared me to sit at night in the Tatar cemetery. And I did it! I wasn’t scared at all. I sat there, not being afraid, for more than an hour!” Hedwig spoke in a loud whisper, excited to tell her brother the news, but not wanting to catch the ear of their mother. Mom would tell the children that, at night, the ghosts of Tatar warriors would emerge through the holes, ready to fight again. It was a long time before Jóska would learn that these “ghosts holes” were actually made by gophers.

Jóska thought for a moment. Sitting in a graveyard for an hour at night? That was brave. However, he could not let Hedwig one-up him. But how could he properly describe his night spent in the wine barrel, while the town’s gentiles beat Jews bloody, burned down their houses and stores?

“I was in a wine barrel all night!” was all he said in the end. Hedwig looked at him sideways and frowned, waiting for more. But her brother did not have the words. He added quickly. “And I was not afraid!”

Hedwig, though, stayed silent and gave his brother a quick hug and a giant pinch on his cheek, turning it bright red.

For a few days, Jóska was overjoyed at this rare treat — his entire family together in one place. But he also noticed nervous glances between his father and grandfather. Whispers in corners, heads shaking. After a few days, Jóska was not surprised when his father and grandfather announced that they must return to Tămașda. They said it was to take care of “business,” but even the children knew there was danger in the old village. They hugged the kids goodbye, Jóska trying his best to hold back tears.

***

Jews in Tămașda and in all the rest of Hungary and Romania were loyal and patriotic citizens of the land of their birth, sending their sons to die in their wars and contributing to the economy. Tămașda was a little village in southern Hungary, an insignificant speck on the Hungarian map, a picturesque village with some outsized sense of historical importance. Here, great battles were waged with the mighty armies of Genghis Khan. And here, according to legend, advancing Tatar armies were stalled. A small fortress with a mutilated steeple still stood as a memorial to this glorious national past.

The village, at the time of Jóska's childhood, consisted of five or six very wide, unpaved streets. Deep in his earliest memories were the blowing gusts of wind picking up the dust in the street, swirling them into patterns in the air. One of these wide, dusty main thoroughfares was called Lovy Street, where you could find City Hall, on the steps of which was the village drummer, who related the news daily. Jóska enjoyed listening to the news, but inside City Hall were also the gendarmes, in their caps, who kept the population in constant fear—especially the Jews.

Across from Jóska's family store was a large village-owned public grounds with schools, churches, a playground, and a soccer field. Once a year, on March 15, there was the Hungarian National Freedom Celebration that always ended in public brawls, which were broken up by the gendarme.

Jóska's earliest clear memory was when he was four years old in the summer of 1913. He was playing in the middle of the street, where visibility was clearest, one eye on the horizon so he could see any oncoming travelers. Then, he heard the call. "They are coming." There was his older brother, Andor, returning for the summer from his religious studies in Paks. He hadn't seen his brother in a very long time, and Jóska ran exuberantly down the street to greet him. Andor was walking with his Uncle Marcus. Jóska, filled with love for his brother, pounced on Andor with a hug. But Uncle Marcus returned the greeting with a hard slap on Jóska's face. He never knew what caused the slap. Perhaps it was simply the look of joy that his uncle wanted to wipe off his face. Maybe nobody, especially no Jew, had a right to be so joyful when greeting a brother returning from Torah studies.

The Lovy family had many real estate holdings in Tămașda and the surrounding countryside, which they visited on Saturdays and holy days. The business property and living quarters were in the center of the village square on a corner lot near City Hall, across from a church and a public school. It was surrounded by a high brick fence with barbed wire on top to deter thieves. On one side of the property flowed a small brook with knee-deep water. Ducks and geese from the village would wade in it. They also had a few dogs on chains, released at night to roam freely. At the entrance was a huge iron gate, locked at dusk and opened at dawn, giving the feeling of security in normal times. The family business was like many others that mushroomed and peacefully thrived and flourished in Jewish hands all over Europe.

In front of the store stood a large tree with dense foliage that was impenetrable to rain or sunshine. At its base was a huge, unrefined block of rock salt, where village animals could make daily visits and have a few licks, compliments of the house, and drink from a public trough across the street.

Also under the tree was a wooden bench and a large table, where strangers often took a rest in the shade. Jóska's paternal grandfather sat there for hours, reading from a large book. Sometimes, two of his cousins kept him company, but they constantly argued. Yet, for some strange reason, they remained friends despite their loud bickering.

The store was large, with two doors and two windows. One was a massive door and serviced as an entrance to the family's living quarters. The other door was two steps higher and led to a korcsma (saloon), a separate building managed by an innkeeper. Two windows located very high in the wall had iron bars. Their sole purpose was to provide light.

The courtyard seemed tremendously huge to little Jóska, and it housed many small buildings—warehouses for merchandise sold in the main store. A skittles (bowling) course, stables, silo, harvester, corn, wine cellars, and many gardens also shared the courtyard. One special small garden was Jóska's grandmother's private one and was her pride and joy. She carefully cultivated exotic herbs such as saffron. For many decades to come, Jóska would often return to this garden not only in his dreams but as the model for the many gardens he planned, cultivated, and tended throughout his long life.

It was in this backdrop of relative comfort and prosperity that Jóska also detected that there was something else going on, something more profound and, at the same time, more precarious. The Lovy family was somehow different, and it had to do with something indefinable. It was just a word. "Jew." It was used to describe who and what they were, defined certain rules and customs, regulations by which they had to live. At first, it was just wonderful stories, like the one about the Golem told to him by his mother, a descendent of Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague, the Maharal, and creator of what could only be the first Jewish superhero.

He was told that it was necessary to live a separate way in order to preserve their identity, their existence. Jóska's brother, Andor, who had been sent to their mother's parents' house in Paks for religious schooling, provided enough answers to last him until he, too, was six years old and able to make the journey for religious education. He learned that the heated arguments of his cousins were actually discussions of the Talmud. Jóska could not wait to be able to speak the strange language of argument and prayer and unlock the secrets to this special place of the mind and spirit.

One night, a knock on the door in that summer of 1913 showed Jóska that this difference was not only spiritual in nature. The rap at the gate, and the excited barking and running of the dogs, woke up the whole house. Outside was the chief of the local gendarmes with a few members of his local force and a pack of customs officers from the district office. The chief, a friend of the family in ordinary times and an enemy whenever it was convenient, informed Jóska's grandfather that a man had reported that "the Jew" was dealing in illegal raw tobacco sales. It was actually the town drunk who reported it, but nothing was more believable or gratifying than to find a respectable Jew dealing in illegal merchandise and put him through personal embarrassment. In some cases, this could mean a few days in jail, a fine, and even twenty-five lashes in a public place. In this case, the accusation was not true and, as far as Jóska's grandfather could determine, was the result of the saloon innkeeper denying the accuser some extra credit.

After an intensive all-night search, nothing was found. Jóska's grandmother treated the whole party to breakfast, sampled some spirits, packed them off with some free merchandise to keep them happy for a little while, and bade them farewell.

***

Tămașda still had been spared violence, but that soon changed when the Romanian government took over the town. That region was suddenly sucked away from Hungary. One day before the Romanian occupation, the local townspeople decided it was time to grab what they could from their Jewish neighbors. Local government authorities gave the nod, and the Tămașda pogrom commenced just as Jóska’s father and grandfather arrived from Paks. What was not stolen was burned to the ground. In one day, all the wealth that Jóska’s family had accumulated over generations was stolen and burned. His grandfather and father, with help from their Jewish friends, managed to barely escape with their lives.

They returned a few days later to their house still smoldering and the courtyard occupied by Romanian troops. Jóska’s father and grandfather complained bitterly to the new Romanian authorities, but complaints gained them nothing but an overnight stay in the local jail. The next day, they were ordered to leave Tămașda. Jóska never saw Tămașda again. But, later, to his grandchildren, the place would take on the mystique of myth, of a lost pre-Holocaust world. Jóska would always speak of Tămașda through the vague mist of a child’s memory.

This was the way it had been for generations. Jews were integral parts of the local economy, but there was always an awareness of how precarious it was. It took the Great War and the upheavals in Hungary afterward, when the country lurched violently to communist revolution, and then to fascism, for the Jews of the land to receive first warning of the dangers to come. Some heard, but many others did not. The magnitude of what was to come first became evident to Jóska when he received word of the destruction and dispossession of his family’s home in Tămașda. Four years earlier, in 1914, the entire population had gathered around the Tămașda’s village drummer, who announced the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

The people reacted joyfully, yelling and crying. Every train had a pompous sendoff. The young men were drunk and singing, like they were going to a family picnic. Eventually, though, the parades died down, the sendoffs grew less exuberant, and death notices came in. So, too, came the first signs of hatred against Jóska’s family. It was well-known that his father was rejected from the army. One night, a window was broken and in the saloon owned by his family, the “rich Jew boy” was the center of conversation. Over time, Jóska would hear the strange voices in the tavern grow louder, harsher, more violent against the Jews and, in particular, toward his father who had somehow avoided the draft.

It was in this atmosphere that Jóska had been sent away to Paks, where the Jewish community was well-established and, until the pogrom of 1918, were safe and prosperous. Slowly, though, a new breed of young anti-Semitic priest began to openly preach hatred against Jews from the pulpit of the local Catholic church.

Still, the local Jewish community was safer than their brethren in the countryside, who fell victim to roaming bands of anti-Semitic terrorists with government approval to victimize Jews. They were the precursors to Hungary’s Arrow Cross proto-Nazi organization.

Meanwhile, the worst the Jewish community in Paks was forced to endure was the annual Easter procession — this one led by a young anti-Semitic priest named Fenyes, who whipped up the local population against “Christ-killers.” It always ended in anti-Jewish vandalism and beatings.

***

Paks had a very active Jewish community life, with about 250 families who had been there since the 1730s. The temple, donated to them by a local nobleman, was built as a fortress on high ground with heavy doors, high windows, and wire mesh protection. The courtyard was surrounded by a very high brick and steel fence. Inside the temple yard was a school, where Jóska would receive his Jewish education for the next 12 years, a mikvah and living quarters for the rabbi, cantor, sexton, and caretaker. There was also a large matzoh bakery, which supplied the Jewish community of Paks and surrounding areas. The bakery operated from early January until one day before Passover.

In the spring of 1919, around Passover, when the matzoh bakery ovens were fired up, the community was happy the harsh winter was behind them. For Jóska and the other children, it was joyous. There were actual guns lying around, with which Jóska’s and friends used to play soldier.

It was a few days before Passover, the workers had been paid and discharged, and the bakery cleaned out. The next few days, the Chasidic members of the congregation took over the factory and baked a special shmurah matzoh, which could be touched only by sabbath-observant people.

The Chasidim were walking from the bakery over to the beth hamidrash (house of learning) for their daily prayers, when they were greeted by an agitated couple from the nearby village of Duna-Kömlőd, one of many German-speaking communities around Paks filled with people who made their living through small farming, where they also carefully cultivated their anti-Semitism. Collectively, they were known as Swabians, or Swabs. Jews employed them, but they were among the first to turn against their Jewish employers during times of pogrom, most recently during Jóska’s night in the wine barrel.

This couple’s daughter had been working in the matzoh bakery for the past few months, and last night she’d failed to show up at home. The Chasidic men managed to convince the angry parents that their daughter had taken her pay and left for the season, just like everybody else. But, the next day, in the late afternoon, a cartload of agitated, noisy young people accompanied the girl’s parents. With them was the priest, Fenyes, still fresh from preaching the people into an anti-Semitic fury during Easter. Also with the posse were some gendarmes and a couple of local politicians, demanding the whereabouts of the sweet Christian girl, Julcsa.

Jóska watched as the synagogue courtyard slowly filled up with people, all shouting an accusation against Jews that Jóska had not previously heard. Oh, he knew about all the myths of Christ killing, money-grubbing, and all else that goes with the Jewish caricature, but nobody had told him before about the “blood libel.”

“It is just like it was in Tiszaeszlár in 1882!” shouted a local gentile scholar. That’s when a 14-year-old Christian girl had gone missing, and local Jews had stood trial on charges of ritual murder. They were accused of beheading her, and using her blood to make matzoh. The local press had whipped the townspeople into a frenzy back then, and the myth of the Passover ritual sacrifice had endured. Today, as Jóska watched the courtyard, he realized the situation was in danger of escalating to blood libel levels.

The Jewish community and some of the city leaders tried to calm down the people and ask for more police officers to search the temple complex, including the matzoh bakery, for the girl, and to keep order. So far, order was achieved. Jóska and the other children were kept together in a group surrounded by older boys and a young man who’d served in the Great War. Almost the entire Jewish community of Paks assembled in the temple courtyard, where accusations and curses were leveled against them. The gendarmes searched with new fervor, but not a trace of Julsca could be found. This was going to be a very long night.

There were two groups of people facing each other, divided only by a few non-Hungarian soldiers. On one side were the Jews, crying, praying, shouting selected curses; on the other side, another group of people (some of whom Jóska knew as their neighbors) yelling, cursing, and shouting threats of murder and extermination. This continued until dark, and only a few soldiers with guns prevented an historically bloody event.

Then, out of the night, from the direction of the main gate, came a shout: “Mom! Dad!” For an instant, the entire courtyard was silent, frozen mid-argument, fists raised, knives, sticks, clubs at the point of being withdrawn from coats. It was Julsca. The first to snap out of the reverie were her parents, running toward the gate. The townspeople were still frozen, almost having forgotten that this melee was all about a missing girl who, apparently, was no longer missing. Evidently, her head was in place, her blood still in her veins and not spicing up the Passover matzoh.

Appearing in the gate, indeed dominating it, was a husky farmer, red with rage, holding and pulling Julsca, about 16 or 17 years old, with one hand, and a boy about the same age with another. They wriggled desperately in the farmer’s tight grip. Jóska heard the farmer utter words he had never heard before, nor could he later find translations for, in any of his grandfather’s dictionaries. The farmer came within centimeters of Julsca’s parents’ faces, and his voice boomed for all to hear.

“How did you raise your daughter?” the farmer shouted, spittle coming out of his mouth and striking Julsca’s father. “She is a whore! Take her home with this boy! I don’t want to see them again or their Swab bastard.” And, with this, the farmer turned around and left for home.

The crowd froze, mouths suspended in mid yell; fists, sticks, rocks, pitchforks still in the air. Then, muttering, they slowly broke apart and found their way through the gates, down the street, and separated, heading into their own homes.

“Grandma?” Jóska said.

“Yes, my little Jóskala? It is over now. Nothing to fear.”

“I know. But, Grandma?”

“Yes, Darling?”

“What is a whore?”

A later investigation found that Julcsa and her boyfriend Pista were both employed at the matzoh bakery. The girl was of Swab origin and the boy was Magyar. The Magyars hated the Swabs, so Pista never took the girl home, but the affair flourished without parental knowledge. The father heard about the missing girl in Paks, and since his son worked there, he grew concerned and set out for the stables to saddle up his horse and head into town. What he found in the stables, though, were animal noises that were not coming from the four-legged ones. Julsca was obviously pregnant. He barely gave Julsca and Pista enough time to dress before dragging them to the temple courtyard and returning Julsca to her parents.

The next few days, the Jewish community kept its doors closed and windows protected. The community was shaken.

For Jóska, it was very educational. He had wondered what the boy and girl had been doing together that made her belly swell. With the help of a few older boys, he had pieced it together. It was a startling realization for a boy steeped in Jewish ritual. Babies came to married mothers and fathers, didn’t they? It was an exciting, forbidden knowledge. But the excitement was also tempered by the look he remembered seeing on the priest Fenyes’s face. It was disappointment. He wanted an excuse to chase the Jews out of Paks once and for all.

Jóska would never forget the chilling look of disgust and hatred Fenyes gave him, in particular. The excitement of sex mixed with dread. Fenyes hated him. Him in particular, it seemed, and Jóska knew that one day he would have to either fight that hatred or run from it. If not from Fenyes, then from others like him. Jóska returned the look. Remembering the wine-barrel pogrom, Jóska gazed at Fenyes with renewed understanding. The priest and the boy locked eyes. Fenyes was the one to look away first.

Thank you for sharing such a wonderful yet heartbreaking story. “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

Powerful, Howard. 😭